Also known as sphinx moths, these little (well, not so little for a moth) cuties are in the Sphingidae family of the Lepidoptera order of the insect world, which includes both moths and butterflies. Perhaps you will remember their brief fling with celebrity following the release of the 1991 film,

The Silence of the Lambs. The gothy Death's-head Hawkmoth had a pivotal cameo role and was featured on the film's theatrical release poster IN FRONT OF THE STAR.

|

| A brush with fame. The 90's were heady days for many of us. |

|

|

Hawk moths are sizable little buggers, with some of them reaching hummingbird proportions. They have rapid wingbeats, and some species are also able to hover like a hummingbird, unlike most other nectar feeding insects, which will typically perch on a flower to extract nectar. Because of this energetically demanding feeding behavior, hawk moths prefer flowers with larger nectar loads, 'cause when you eat on the run you really want to get the biggest bang for your buck.

They are also typically nocturnal or crepuscular (active at night or

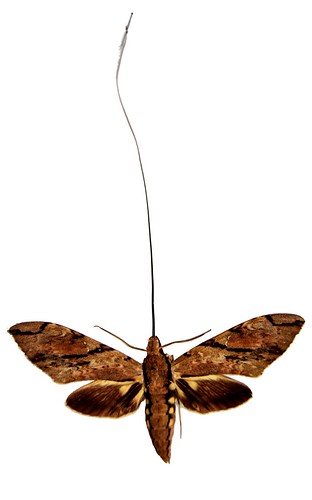

twilight). As such, the flowers that they select often have a predictable host of characteristics that attract hawk moths, such as pale or white flowers that open and produce nectar at night, a tubular petal morphology, nectar spurs, and a robust fragrance, so that the flower provides strong visual and scent cues. As you can see in the picture below, the moths have a long, thin

proboscis, which is basically like having a long sipping straw for a mouth.

What's cool is that there is a correlation between hawk moth proboscis length and the length of the petals (or corolla) and nectar spurs of the plants they pollinate. Why? Because there's an evolutionary "motivation" for the plants to match lengths. Generally, there's a sort of helpful relationship between plant and pollinator: the plant makes nectar for the pollinator to eat, and the pollinator either distributes pollen onto a flower's "swimsuit area" so that fertilization can occur or carries pollen off to another flower. If you're a flower with a short corolla and a pollinator with a super long proboscis takes your nectar there is no way for the pollinator to make enough contact with you to make a pollen swap, so you will not reproduce, and your short-petal genes get voted off the island.

There's a fun story about Charles Darwin getting a box of orchids in the mail one day for his studies. In the box was an orchid found only in Madagascar (

Angraecum sesquipedale) with a nectar spur that was like, 12 inches long. Darwin was intrigued. The whole point of a plant's nectar, basically, is to attract a pollinator, so what the heck was the point of a crazy long nectar spur, given that Darwin was not aware of

any pollinator with equipment long enough to get to the nectar at the bottom of it? Long story short, he predicted there was some moth, probably in the Sphingidae family, that pollinated this orchid. And sure enough, about a half century later,

Xanthopan morgani was identified:

Isn't that sweet? A natural selection love connection. So now you know a little bit more about giant moths than you did earlier today. How about a super adorable hawk moth pic to sign out???

|

| Don't you want to just rub his furry back? Cute lil bastard... |

No comments:

Post a Comment